After over three years of research, writing, and review, our new book, Learning Agile, is finished! Jenny and I are really excited about it, and we think it’s our best work yet.

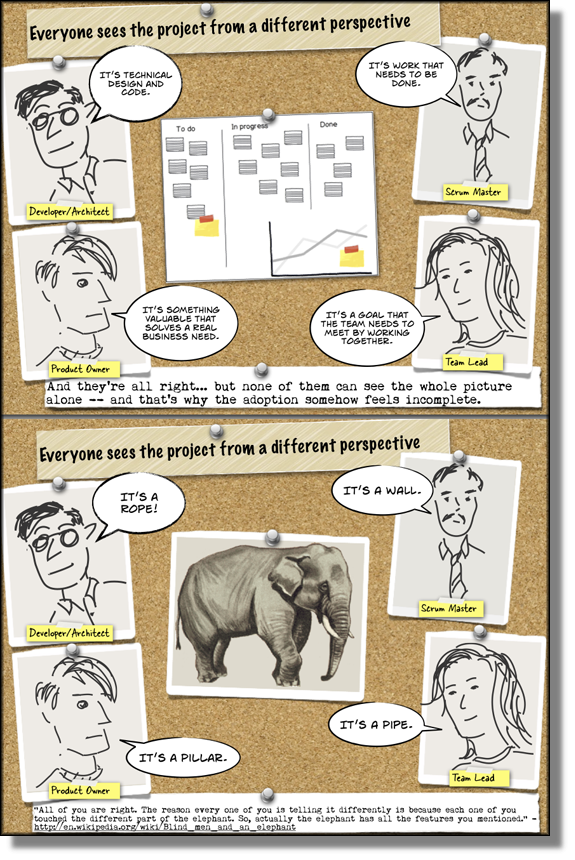

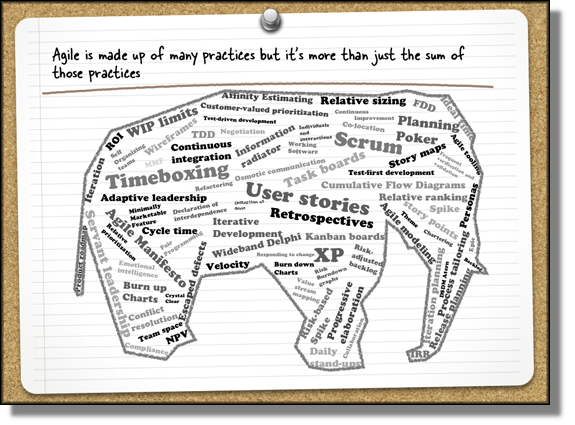

We write this book because we really want you to learn agile! Agile has revolutionized the way teams approach software development, but with dozens of agile methodologies to choose from, the decision to “go agile†can be tricky. This practical book helps you sort it out, first by grounding you in agile’s underlying principles, then by describing four specific—and well-used—agile methods: Scrum, extreme programming (XP), Lean, and Kanban. Each method focuses on a different area of development, but they all aim to change your team’s mindset—from individuals who simply follow a plan to a cohesive group that makes decisions together. Whether you’re considering agile for the first time, or trying it again, you’ll learn how to choose a method that best fits your team and your company.

Here’s what you’ll learn in Learning Agile:

- Understand the purpose behind agile’s core values and principles

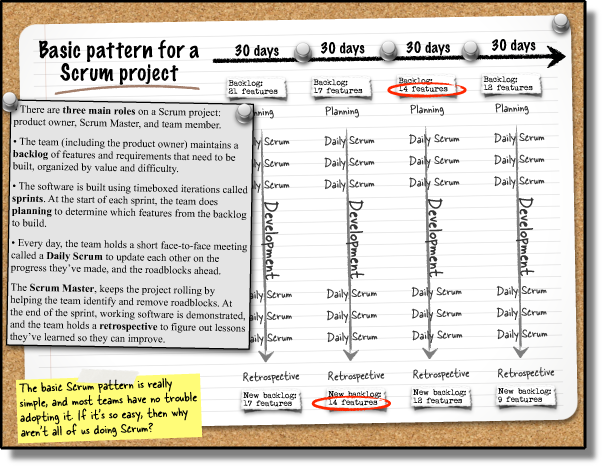

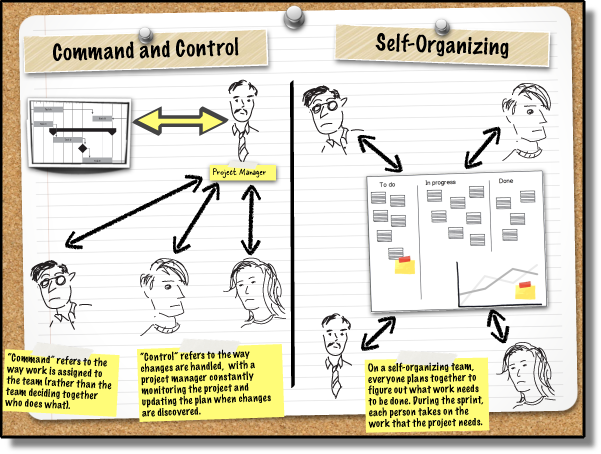

- Learn Scrum’s emphasis on project management, self-organization, and collective commitment

- Focus on software design and architecture with XP practices such as test-first and pair programming

- Use Lean thinking to empower your team, eliminate waste, and deliver software fast

- Learn how Kanban’s practices help you deliver great software by managing flow

- Adopt agile practices and principles with an agile coach

We’ve already gotten some great praise. Here’s what other people have to say about it:

Another amazing book by the team of Andrew and Jennifer. Their writing style is engaging, their mastery of all things agile is paramount, and their content is not only comprehensive, it’s wonderfully actionable.

—Grady Booch – IBM FellowWhat Andrew and Jenny have done is create an approachable, relatable, understandable compendium of what agile is. You don’t have to decide in advance what your agile approach is. You can read about all of them, and then decide. On your way, you can learn the system of agile and how it works.

—Johanna Rothman – Author and Consultant, www.jrothman.comAn excellent guide for any team member looking to deepen their understanding of agile. Stellman and Greene cover agile values and practices with an extremely clear and engaging writing style. The humor, examples, and clever metaphors offer a refreshing delivery. But where the book really shines is how it pinpoints frequent problems with agile teams, and offers practical advice on how to move forward to achieve deeper results.

—Matthew Dundas – CTO, KatoriAndrew Stellman and Jennifer Greene have done an impressive job putting together a comprehensive, practical resource that is easily accessible for anyone who is trying to ‘get’ Agile. They cover a lot of ground in Learning Agile, and have taken great care to go beyond simply detailing the behaviors most should expect of Agile teams. In exploring different elements of Agile, the authors present not just the standard practices and desired results, but also common misconceptions, and the positive and negative results they may bring. The authors also explore how specific practices and behaviors might impact individuals in different roles. This book is a great resource for new and experienced Agile practitioners alike.

—Dave Prior PMP CST PMI-ACP – Agile Consultant and TrainerAndrew Stellman and Jennifer Greene have been there, seen that, bought the T-Shirt, and now written the book! This is a truly fantastic introduction to the major Agile methodologies for software professionals of all levels and disciplines. It will help you understand the common pitfalls faced by development teams, and learn how to avoid them.

—Adam Reeve – Engineer and team lead at a major social networking siteThe biggest obstacle to overcome in building a high-performance agile team is not learning how, but learning why. Helping teams discover the why is the key to unlock their potential for greater commitment and more creative collaboration. With a focus on values and principles Andrew and Jennifer have provided an outstanding tool to help you and your team discover the why. I can’t wait to share it.

—Todd Webb – Technical Product Leader at a global e-commerce company

You can read the first chapter for free in the Free Sampler PDF.

Learning Agile is available directly from O’Reilly, where you can buy the paper copy, a DRM-free eBook, or a great deal where you can get both for a discount. It’s also available at Amazon.com and all major retailers.