I’ve met a lot of programmers who really hate project management. And it’s not that surprising, because project management done poorly can be a pain. But if you’re a developer looking for a job, employers are more and more likely to expect you to know something about project management. Luckily, good project management can make your life easier, and it’s worth knowing about it—not just for job interviews, but to help you get the most out of your own projects. In part 1 of this post, I talked about a few basic things that I think every developer ought to know about project management. Now I’ll finish up by going into a few details that can help you run your projects more smoothly—and deliver better software.

Why you should care about project management

I’ve had a lot of developers over the years tell me outright that they think project management is stupid.

Some of the best developers I’ve worked with had pretty negative opinions of project management. At best, they’d say something like, “Well, that sounds good for another team, especially a really big team, but our projects run just fine without the extra overhead.†At worst, they think it’s malignant bureaucracy imposed on them by pointy-haired bosses. One bad experience can sour a good developer on project management. And that’s pretty unfortunate, because good project management can make a developer’s life a lot easier.

So why should a developer care about project management? I think the answer is in the Why Projects Fail talk that Jenny and I have done many times over the years, where we outline many different ways that projects fail. We got the idea from that presentation because we’ve spent years talking to many different people about the different kinds of project problems. We had to figure out exactly what it means for a project to fail. Obviously, if your project completely crashes and burns, it’s a failure. But the funny thing about a software project is that you can almost always deliver something – even on a project that everyone agrees is a failure, you’ll have code that compiles and runs.

So we came up with this definition of project failure:

- The project costs a lot more than it should

- It takes a lot longer than anyone expected

- The product doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do

- Nobody is happy about it

When we go through these things, we always get a lot of head-nodding, especially from developers. More importantly, we’ve never met a single professional software engineer with more than a few years of experience who hasn’t been on at least one failed project. We always ask for a show of hands to see if there’s anyone who’s never had a failed project. And we’ve yet to meet anyone who has. (We did get someone who raised his hand once, but I talked to him afterwards, and he was just messing with us.)

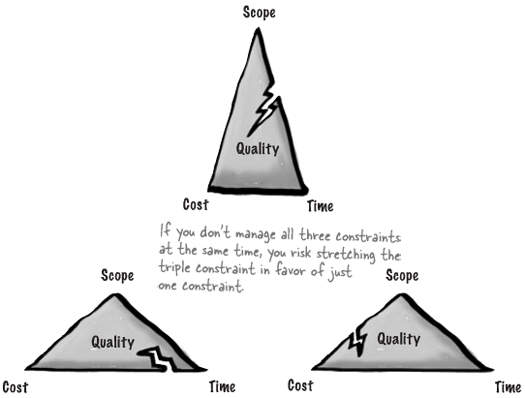

What does this have to do with project management? Well, everything! Have a look at a typical project management textbook, and you’ll learn about the “triple constraint†(which some people call the “iron triangleâ€) of scope, time, and cost.

(source: Head First PMP, 1st ed., O’Reilly 2007)Project management really boils down to managing that triple constraint: balancing the scope of the work to be done, the cost of doing the work, and the time it takes to get the work done, all in order to get the best quality that you can. If you do that right, your project runs well, and your team is happy. If you do it badly, your project stinks, and you end up with a failure. And that’s why you, as a developer, should care.

I’ll go into a little depth about each of those things – scope, time, cost, and quality – just to give you an idea of why you should care about each of them. But the one that developers care about most is scope, so I’ll spend a little more time on that first.

Scope: the work and features that go into the project

Every project can be broken down into a small number (say, ten to twenty) features. For big projects, those features are big (“solid rocket boosters,†“reuse and reentryâ€); for small projects, those features are small (“holds 12 fluid ounces of liquid,†“screw-top capâ€). And similarly, every project can be broken down into a small number of tasks that are needed to build those features. Project managers call the list of features the product scope, and they call the tasks the project scope – and a lot of people just talk about all of it as scope.

I’m consistently amazed by how much work a project team can put into a project without before they realize they’ve got a scope problem. Jenny and I talked about this in our book Applied Software Project Management in the section on scope problems:

A change in the project priorities partway through the project is one of the most frustrating ways that a software project can break down. After the software design and architecture is finalized, the code is under development, the testers have begun their preparation, and the rest of the organization is gearing up to use and support the software, a stakeholder “discovers†that an important feature is not being developed. This, in turn, wreaks havoc on the project schedules, causing the team to miss important deadlines as they frantically try to go back and hammer the new feature in.

Does that sound familiar? If so, talking about the scope earlier in the project can really help. One way to help fix this is to put together a Vision and Scope document. It’s a really simple document, usually only a page or two, but it can really help prevent scope problems. It’s also a staple of project management. Once in a while, I’m pulled into a project that’s been running into trouble. I’ll spend a few hours talking to each of the team members, managers, and anyone else I can find who knows something about the project or needs it done. I’ll throw together a quick vision and scope document, and what I’ll often find is everyone had very different ideas of what would actually get built. And it’s usually a big relief, because everyone – especially the lead developers! – realizes that they were going down a path that would have had them waste a lot of time building the wrong software.

(source: Head First PMP, 1st ed., O’Reilly 2007)

Faster, better, cheaper—choose two… right?

There’s a whole lot more that I’m tempted to write about managing time, cost, and scope in order to get to the right quality level, but I really want to pare this down to the basics. There’s an old (and somewhat cynical) project management saying: “faster, cheaper, better: pick two.†What it means is that there’s no way to reduce cost, shorten the schedule, and increase quality all at the same time. At least one of those things absolutely has to give.

But there’s a reason that’s a saying and not a law! All three of those constraints are related to each other, and there’s almost never an easy, obvious trade-off where you can sacrifice one to improve the other two. If there were, project management would be a lot easier. It’s really easy to fall into a trap of trying to do the impossible, but the first step in avoiding a trap is knowing that it’s there. In this case, just knowing that every project is a balancing act between scope, time, and cost is a really good first step in making sure your project ends up running well.

I wanted to leave you with just a couple of thoughts:

- One thing that makes the “time†aspect of project management tricky is that developers really hate giving estimates – or, more specifically, they hate giving estimates because they know they’ll be misinterpreted as hard commitments. I wrote a blog post about this a while back (The Perils of a Schedule) .

- Every project needs a start, middle, and end. My old friend Scott Berkun writes about this beautifully in his book, Making Things Happen.

- Cost doesn’t have to mean dollars – it’s often more effective to measure cost in hours.

- Burndown charts really help, because they can make the cost seem real.

- Sometimes the word “quality†makes developers a little nervous, because they start to think that improving quality just means doing endless testing. Sometimes it helps to replace a phrase like “high-quality software†with “software that we can be proud of.â€